By John Hargraves.

My sister Elaine is a graveyard sleuth. I learned this by spending time traipsing through cemeteries with her. She’s the family historian and arranges artful pedigrees of our genealogy. She traced our paternal line back nine generations into the 1700s with six Johns. At the head was a John, then a William, and then James and Harold landed in between the rest of the Johns.

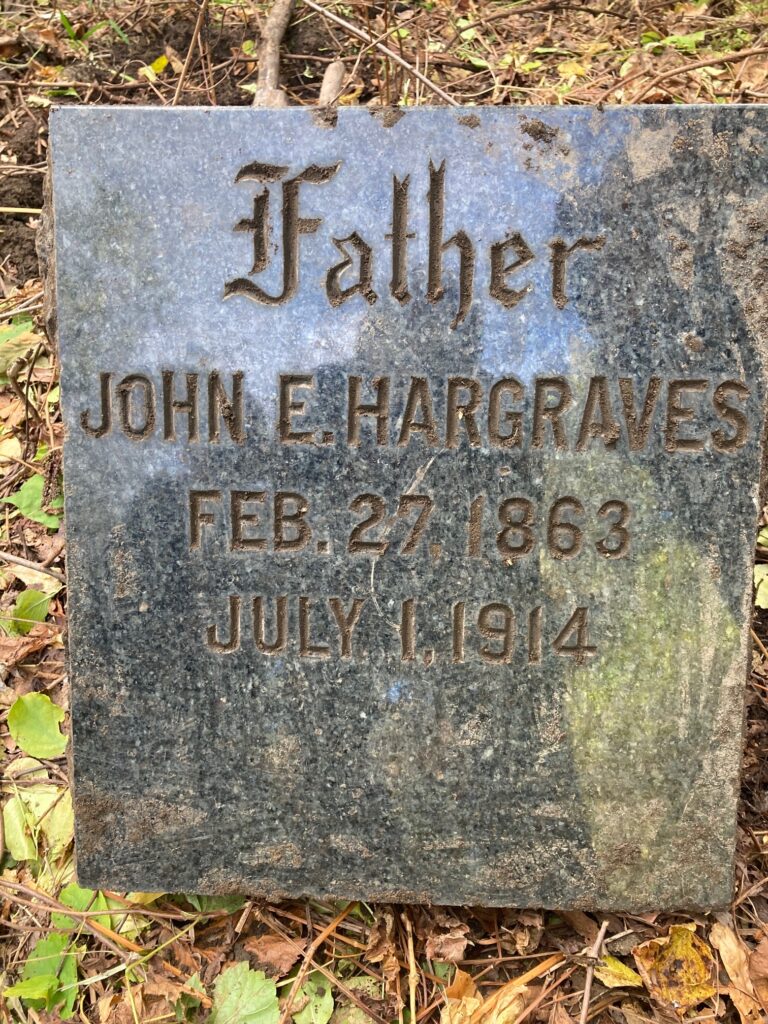

Her studies brought us to Vale Cemetery in search of the forgotten grave of our great grandfather, John E Hargraves. He, like many of the other Johns and forefathers, succumbed early from cardiac issues. My father, a John, plagued by his heart and long gone himself, never knew of the exact whereabouts of his namesake’s resting place. The Johns were frequent and more attention should have been made to name them like kings. Then I would’ve been John V instead of a Jr. And Johnny, my son, would enjoy the regal or even papal John VI instead of the III which rightly belongs to great grandpa. Then again, if Elaine does any more research, we’ll all be playing Roman musical chairs with these ordinal numbers.

Historic Vale is a growing place in the heart of Schenectady. It’s filled with all kinds of burial plots, plaques, stones, vegetable gardens, rabbit hutches and an outdoor sanctuary where the Clergy Against Hate gather. There’s even a special section that’s ecofriendly for self-composting, where bodies can nurture trees and ruminants landscape the grass. As the old saying goes, people are dying to get in.

Last fall, two weeks before Halloween, we stopped at the Vale caretaker’s office for records and directions. Analog card files were the only means for locating great grandfather and they were vague. They pointed us to a remote section of land across a forgotten bridged walkway overlooking a disheveled clearing. There stood a tall worn pedestal topped by a shrouded urn surrounded by fallen stones along the woods edge. They say the shroud symbolizes the parting of the veil between this world and the next.

Deeper into the trees was an unoccupied homeless encampment complete with a full hanging clothesline. We approached with care and searched the forest edge. Our team also included my brother-in-law, my niece and her husband, Dave, a strong, sharp-eyed and stalwart fellow. There he spied, lying face down, several old granite stones in the muck of the last century. Using broken tree branches as levers and Dave’s strong back, we resurrected the markers and beheld their exposed polish. Shining was great grandpa John III, dead at the age of 51 in 1914. Next to him we found Emily, his daughter, dead before him at the age of 24 in 1912 and a likely contributor to his heart’s failure.

Leave a Reply